Over on Lemmy (the more chill version of Reddit), a user recently expressed frustration with the lack of a distinction between graphic novels — stand-alone books told in the comics format — and the trade paperbacks that are essentially collected editions of ongoing, monthly (usually superhero) comics. In the course of responding to it, I got off on kind of a rant, and it started to feel like something I should share here.

So, here we go, let’s get into why I really, really don’t care about the fact that people walk into Barnes & Noble and call Batman vol. 12: The City of Bane Part 1 a “graphic novel.”

In the original post (which I won’t link, as it’s hardly an original thought and I wouldn’t want anybody to pile on this random guy), the user says that The Boys straddles the line between being comics and graphic novels, since it was published in serialized format and it isn’t just one story, but it’s a complete story with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

On the contrary, I would argue that the distinction between graphic novels and collected editions is a largely meaningless one, and that the example of The Boys is helpful in illustrating why.

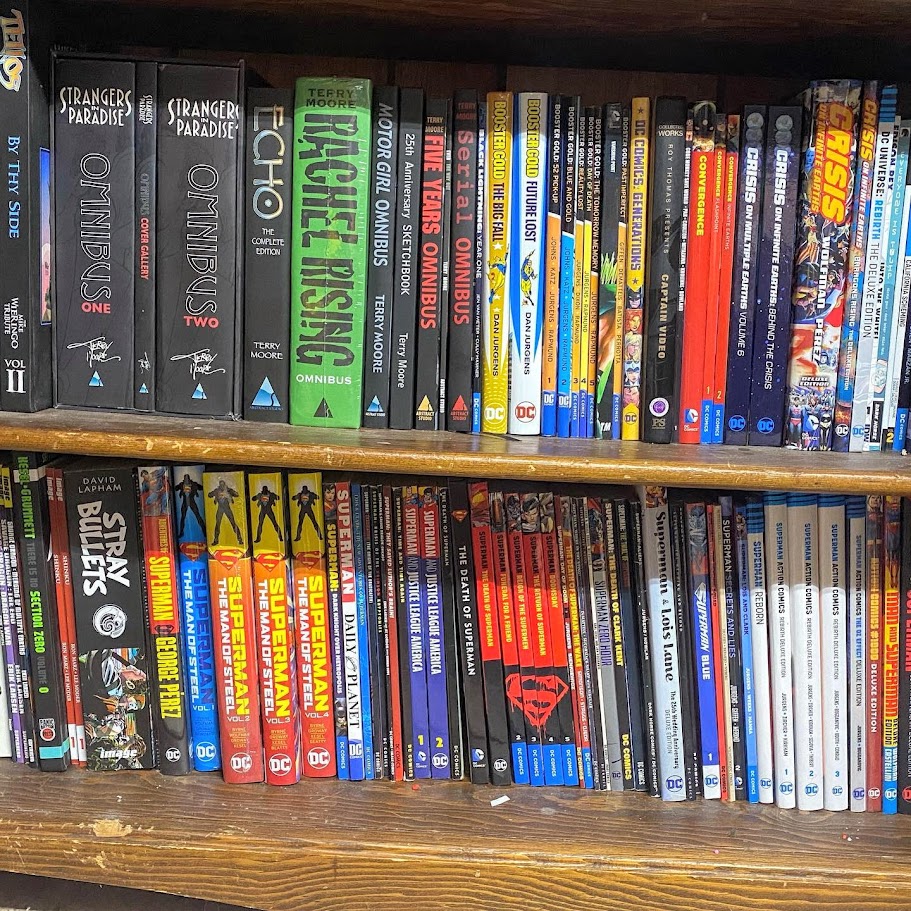

Yes, taken as a whole, The Boys is a story with a beginning, middle, and end, but it was told in a serialized format over the course of a decade or so (2006 until 2012, with spinoffs and such). If that’s a “graphic novel,” then why would the Triangle Era of the Superman books (which is a distinct take on the character and ended up having a beginning, middle, and ending) qualify?

More often than not, a modern collected edition of serialized comics is formatted in such a way as to make it a satisfying stand-alone read, because the bookstore market has become an important piece of most publishers’ business model. If the story is self-contained and satisfying in its own right, but sets up the next installment with a cliffhanger, it becomes hard to argue in good faith that such a book is different from any other book in a series — comics or prose.

Jimmy Palmiotti and Justin Gray’s long run on All-Star Western is one of the best DC comics of the last 20 years, and the run had a definite beginning, middle, and end — but the ending was only something they came up with when the book was cancelled. It would have run forever if it could have, and eventually another creative team would have taken over. If the defining characteristic of a graphic novel is that it’s part of a book series with a distinct start and finish, where does All-Star Western fall? Or Jeff Lemire’s Frankenstein: Agent of S.H.A.D.E.? The list could go on.

The original sin of all of this thinking goes back to the ‘80s and all the initial “POW! Zap! Comics aren’t just for kids anymore!” headlines. Legacy media and educators weren’t comfortable talking about Watchmen, Maus, and The Dark Knight Returns as comics (which they are) and applied the “graphic novel” label to those works based purely on vibes. Comic fans and publishers, desperate to be taken seriously, embraced the approach.

The term “graphic novel” goes back much further, having been coined in 1964 in a fan zine. It gained wider use and mainstream acceptance after Will Eisner used the phrase to describe his beloved book A Contract With God. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that mainstream comics publishers really embraced it, in large part as a way to distinguish their collected editions from single-issue comics when marketing to people outside of the comics fandom.

Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons and Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns were both pitched to the publisher as stand-alone stories that could functionally be viewed as graphic novels, but ultimately were published in serialized comics format because of the demands of the comics industry. How does that factor in?

On the other hand, both of those comics are very formally complex*, and so it’s difficult to imagine the creators did not make changes specifically to accommodate the serialized publishing format. Such changes would fundamentally change the end product in a way that would not have happened, had the books been released in a stand-alone format. The medium is the message, after all.

If I were to care about the distinction — and, broadly speaking, I don’t — I would argue that only books whose original presentation was as a singular work are “graphic novels,” and anything that was originally serialized is a “collected edition.” The fact that creating such a distinction would remove Watchmen, The Sandman, Kingdom Come, Maus, and other similar stories from “the canon” of graphic novels would be seen as undesirable by basically everyone — and to me, that is illustrative of how meaningless the distinction is. I have seen a number of different arguments as to what should or should not “count” as a graphic novel, but at some point it’s all just cherry-picking.

Batman: Hush and The Death of Superman are serialized comics stories that were conceived and executed as fairly stand-alone installments but released as part of ongoing, never-ending comic book titles. Those stories were “collected editions” right up until their cultural cache and sales numbers transformed them — as if by magic! — into graphic novels.

If your definition insists that anything “serious” is a graphic novel and anything “frivolous” is just comics, then you’re giving away the ruse. Ultimately, comics is the art form. It’s the medium. “Graphic novels” is a product category. As such, the publishers who are selling those products reserve the right to define the term.

*It is absolutely worth checking out Shitty Dark Knight and Shitty Watchmen, from Dave Baker and a host of other artists, to see how much the formal storytelling elements are important to conveying the message of these comics. Even with “shitty” art and few-if-any word balloons, the storytelling is so clear that the comics are comprehensible. The Shitty books are, in and of themselves, interesting formalist exercises that help shine a light on the comics form.

Leave a comment